Electric Hydrogen becomes a developer

3rd-party development doesn't work for innovation

Electric Hydrogen raised almost $800 million to build better hydrogen electrolyzers, not to become mired in permitting and offtake negotiations. Yet on September 8, 2025, they announced their acquisition of Ambient Fuels, a hydrogen project developer1.

The deal reflects an unavoidable reality: when it comes to innovative infrastructure, startups often can’t wait for 3rd-party developers to deliver bankable projects and must become developers themselves.

In this post I’ll walk through why Electric Hydrogen had to make this acquisition now, and why this pattern repeats across similar sectors.

Thesis: 3rd-party project development requires maturity

Electric Hydrogen has secured ~$798M in funding to-date2, and are already deploying their systems at sites like Infinium’s Roadrunner eFuels plant in Pecos, Texas. They could have just worked with Ambient Fuels if they wanted, along with any other developer.

So why make this acquisition?

Electric Hydrogen’s customer pipeline likely couldn’t deliver the project volumes they wanted3 due to a lack of viable 3rd-party hydrogen projects. Electric Hydrogen thus needs to develop their own projects to keep momentum going and prove out their technology.

Without this, they were likely to succumb to the global headwinds against hydrogen; with this, they have a shot of pushing through the valley of death to the other side.

To illustrate why this happened, we can look at a sector where 3rd-party project development works relatively well: utility-scale solar.

For large solar projects in the US, project developers4 will identify and secure land for their project, design the system (at increasing levels of detail), shepherd the project through permitting (including environmental review), apply for interconnection (and pay for grid upgrades if necessary), select an EPC5 for construction, procure the underlying equipment, negotiate a power-purchase agreement (PPA) with a utility / independent power producer / corporate buyer, secure financing (including tax credit transfers) from project financiers (based on the projected costs and secured PPA), line up insurance on the system (as necessary beyond warranty), oversee construction, and turn the system on.

That’s a lot of activities, but they are pretty specifically not betting on whether the panels work.

Solar PV is a mature technology. The panels have predictable performance over a 20-year life6, and can be secured from any number of competitive suppliers. The PPAs are negotiated to match the asset life. The EPCs have experience doing this work, and are willing to take on lump sum, turnkey contracts with wraps. The asset managers and pension funds that back these projects know what they are getting from a risk and return perspective7.

Importantly, neither a shovel of dirt is turned nor the bulk of the money committed for a project until the project has reached ‘final investment decision’ (FID).

Nothing gets built until every box is checked. The design, permits, land options, interconnection studies, PPAs, EPC agreements, and capital stack are all known in advance of the commitment of ~80-90%+ of overall project costs. This minimizes absolute risks, while allowing for capital-efficient developers to drive the process.

In utility-scale solar, project development is a business of predictably manufacturing assets with a known and desirable set of characteristics, not of taking technology risks8.

Antithesis: Innovative projects misalign incentives

How does that model translate to sectors that are seeing technical innovation?

Not particularly well, and that’s a problem for the Electric Hydrogens of the world.

Folks like Electric Hydrogen (and their VC backers) would prefer to focus on scaling and deploying their breakthrough innovations, not chasing down permits or selecting EPCs.

The latter was likely deemed ‘outside their core competency’9.

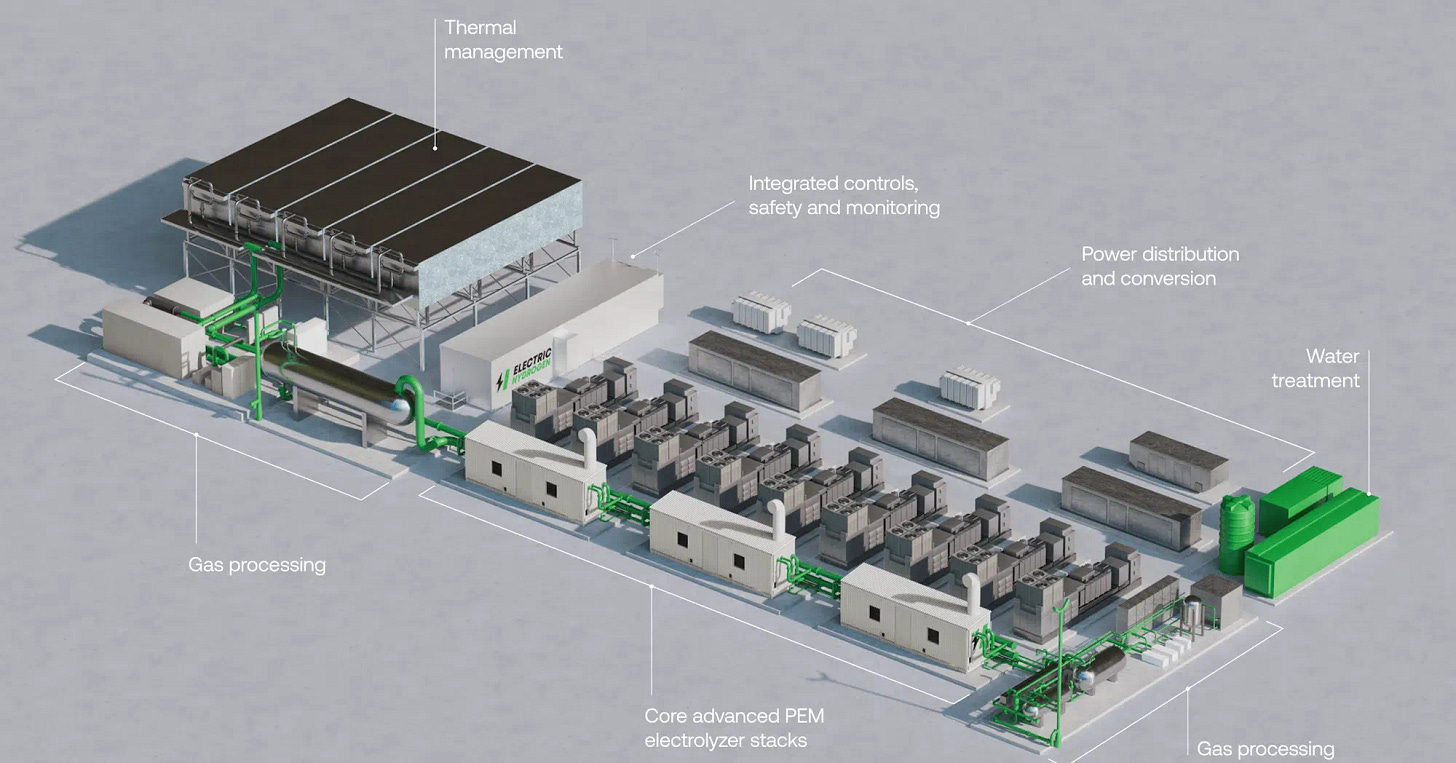

It likely seemed risky enough to develop a series of breakthrough innovations, design something as complex as a ~100MW PEM hydrogen electrolysis plant, make the design repeatable and scalable, manufacture the underlying equipment and subcontract for key balance of plant components, and oversee deployment and integration at customer sites.

Having to actually develop the projects is a completely different set of skills, and there are alluring examples like solar near-to-hand that show those skills profitably existing within distinct entities.

Unfortunately, it just doesn’t work. Worse, it actually can’t work due to the incentives involved.

The challenge here is threefold.

Risk-averse backers

Project finance and infrastructure investors are in the business of, to a first approximation, never losing money. Unproven technologies are risky, and the bar for a technology to become proven is closer to ‘has already been deployed 3+ times in this configuration at this scale’ than anything that might seem reasonable to the uninitiated.

Asymmetric upside

Under conditions of technical innovation, the upside for the project developer and the project-level backers won’t match the the technical innovator, creating a problematic misalignment of incentives.

The first few facilities will be incredibly valuable for the technical innovator, because they (hopefully) prove out the new technology and the learning curves that had to-date been just ambitions. But under normal conditions, a 3rd party developer and project backers don’t see any of this upside. They are limited to the returns from their individual project. Those returns can still be high if the technology truly is a breakthrough, but it’s generally the difference between a 18% and 30% return, whereas a startup might see their value double or more overnight with the successful deployment of a first-of-a-kind facility.

For project financiers, chasing that higher return in the face of technical risk can feel like picking up pennies in front of a steamroller: not worth it.

This is true even for in-house development by a build-own-operate player with a strong balance sheet. Classically, this is the model used in developing deepwater or otherwise remote oil reserves. Only the Exxons and Equinors of the world can carry the complexity and risk of developing big, technically innovative projects. But even balance-sheet developers face the same asymmetry, and true arms-length deals are relatively rare.

Paradox of promise

Perhaps counterintuitively, in shifting commodity markets like hydrogen and SAF it can be just as hard for project developers using proven technology if someone else is promising technical innovations.

Why would anyone sign a 10-year offtake agreement for low-carbon hydrogen at $4.50 per kg today if there are multiple other players promising $3 per kg in ~2-5 years? In a commodity market, if the latter turns out to be real it will disadvantage the early movers.

This paradox of promise from competing approaches, even if unproven (or unrealistic), can gum up the customer pipeline for developers like Ambient Fuels.

—

Take all this together, and 3rd-party project development works in conditions of technical maturity, as in utility-scale solar. While the technology is still being proven out, the 3rd-party model is hard to square.

The upshot: Electric Hydrogen risks having no customers, no matter how good their offering in isolation.

Synthesis: Internal project development for innovation

So Electric Hydrogen had to act. Projects weren’t maturing fast enough to be their customers, and so they needed to do it themselves.

In order to control their fate and prove out their approach, they need to develop their own initial projects. In parallel, 3rd-party developers like Ambient aren’t particularly viable without access to differentiated technology, and are ripe for the picking.

In this context, the acquisition of Ambient makes perfect sense.

The combination strengthens Electric Hydrogen’s development capabilities immediately, and allows them to maintain forward momentum during a critical development window before the current 45V begin-construction deadline on Dec 31, 2027.

Ambient Fuels (and their backers) gets access to a leading hydrogen technology that can be slotted into their projects, allowing them to deploy their capital against a proprietary stream of high-potential projects, while also maintaining exposure to upside as the tech gets proven out.

The biggest surprise is that it took so long.

Electric Hydrogen's acquisition of Ambient won't be the last. Watch for other climate startups to follow suit, or be acquired themselves.

Further reading:

Unlocking Capital for Climate Tech - Breakthrough Energy Ventures

First-of-a-Kind series by Sightline Climate

First mentioned here as part of the Terraform Industries deep dive.

Per Crunchbase

I have no inside info here, and from what I can surmise Electric Hydrogen is well-regarded, there are just broader headwinds facing the hydrogen industry right now.

Because this is an enormous industry, there are niche software tools and sub-contractors to help all along the way, from detailed engineering and design packages through weather and solar irradiance forecasting to system inspection and maintenance providers. Some project developers even specialize in early-stage development (focused on land acquisition, basic engineering, and interconnection) and sell their partially developed projects to larger players.

Engineering, procurement, and construction. Depending on the project, these folks might help with all three legs of the stool, or just one. There is a lot of fragmentation and overlapping models that I am eliding here for generality.

They have an expected degradation curve (beyond which a manufacturer warranty might kick in) and predictable maintenance schedules and costs (with potential for insurance against things like hail).

Tariffs and tax credit changes may create short-term volatility, but this is generally known at FID for any individual project.

This ties into Jerry Neumann’s point about productive uncertainty, wherein 3rd party project developers are not in the busines of taking technical risk.

Put differently, they don’t see themselves as vertical integrators (to use Packy McCormick’s coinage)

Do you think company like net power would benefit from similar move?